Rediscovering Blair Fairchild

A forgotten composer, a fascination that wouldn’t fade

Rediscovering

Blair Fairchild

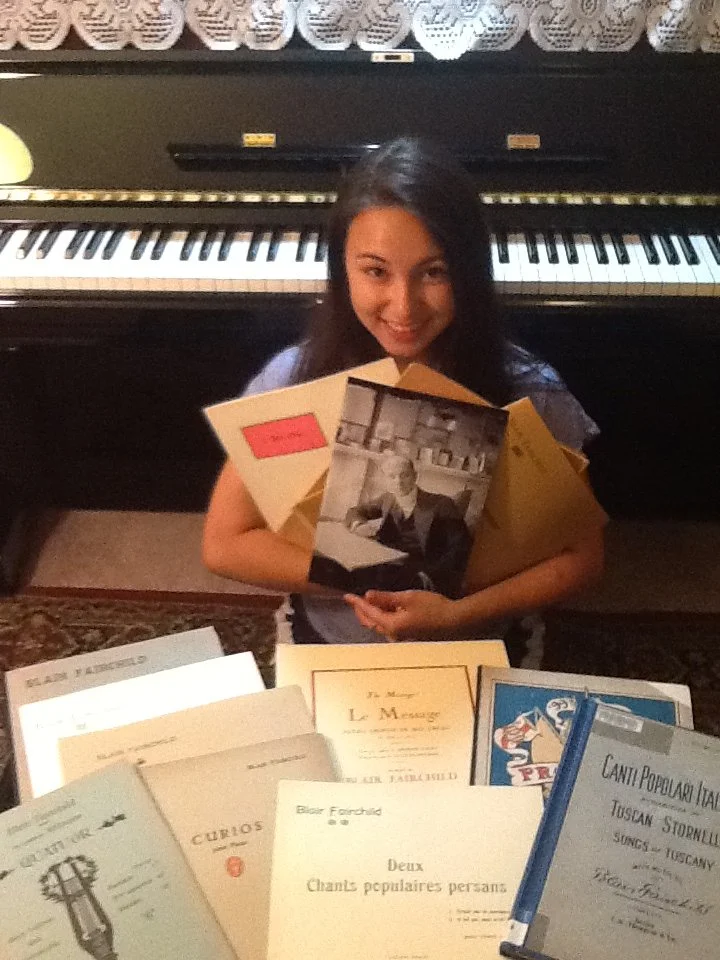

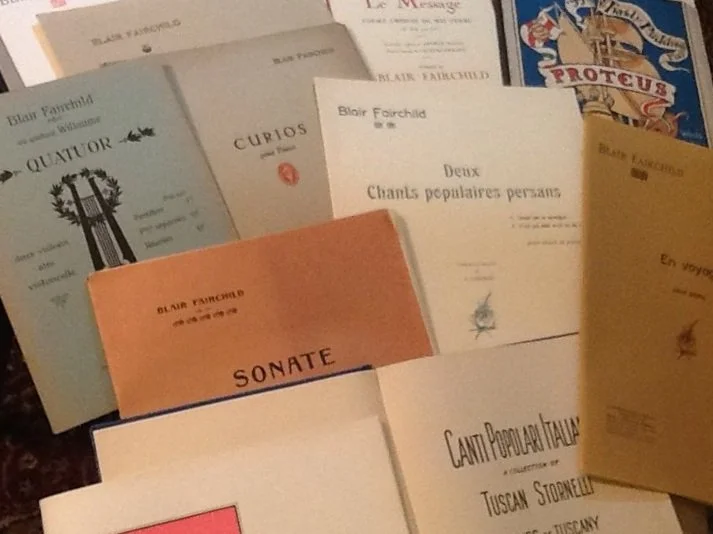

My dad, David, and I discovered Blair Fairchild when I was 15 years old and looking for free duet music on IMSLP. When I went to search for recordings on YouTube, I came up surprisingly empty. We figured that there were two likely possibilities: that his compositions just weren’t good, or that perhaps history had forgotten a composer worth remembering. Sure, maybe his rediscovery wouldn’t be as canon-shifting, earth-shattering as the revival of Bach, but perhaps he didn’t deserve to be lost forever, either. At least, now that the first ever recordings of some of his works exist, you can decide for yourself.

Maybe you’re wondering…

-

There are really three parts to the answer to that question.

First, of course, is the music itself that Fairchild composed. While the appreciation and assessment of classical music is admittedly a very subjective thing, we found as we explored and performed Fairchild’s music that it was attractive not only to us but also to other musicians and to audiences. The pianist Dina Kosten called his music “beguiling” and we agree! We’d be happy to discuss Fairchild’s music—which ranges from songs to chamber music to orchestral works—in more detail if you like.

Second, there is the musicological perspective. Fairchild first studied composition under John Knowles Paine at Harvard but for 30 years was closely embedded in the musical milieu of Paris during the first decades of the 20th century. He had close associations with the composers working there, and we were surprised to discover that influential figures like Nadia Boulanger and Reynaldo Hahn considered Fairchild the best American composer of the time.

And finally, there is a fascinating story to be told about Fairchild’s life and family, about the friendships he cultivated not only with musicians but with artists such as John Singer Sargent and writers including Robert Louis Stevenson and Edith Wharton, and his lifelong appreciation of Persian and other cultures. Rarely an advocate for his own music, he was a devoted mentor and financial sponsor of other musicians, particularly during the First World War.

As we began to understand the full picture of Blair Fairchild’s life and music, and especially his unique contributions to the history of twentieth-century music, it was not difficult to take the step of committing to a long-term project of bringing Fairchild and his music into the light!

-

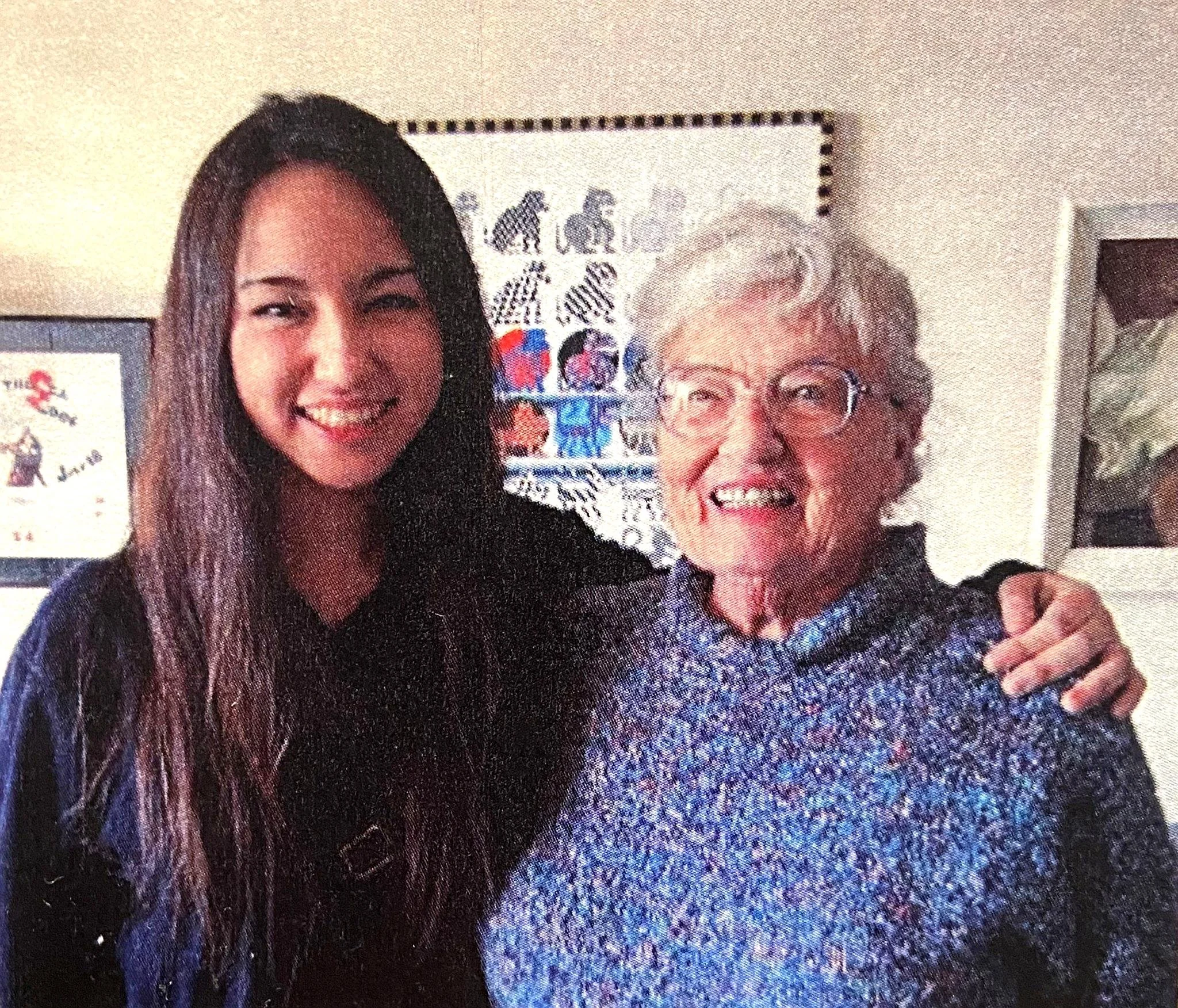

In 2013, near the beginning of the project’s life, we tracked down Blair Fairchild’s closest living relative– Lucia Miller, a Chicago-based artist named after Blair’s own sister, who was Lucia’s grandmother. The initial snail-mail letter we sent to her, introducing the project and our interest in it, was met by this heartfelt response: “Your letter, your wonderful letter, finally reached me here on an island in Maine yesterday… I am startled delighted, and interested by your letter… It sounds to me as if you already know more than anyone else, anywhere, about Blair Fairchild! ... I am deeply impressed by your letter and by your choice of this subject.”

So began a relationship with Lucia that included visits not only to her Chicago apartment but to her home on Monhegan Island off the coast of Maine. She told stories, provided photos and letters, listened to Fairchild’s music played live in her living room, and became a true friend to us in the process. Our relationship with her began in 2013 and lasted until her passing in 2019. Meeting Lucia, and getting to know her, has been the most unexpectedly delightful part of this project. Her lively encouragement of our efforts continues to inspire us to share her family’s story with the world.

-

While, of course, we can only speculate based on our musicological knowledge and understanding of the Western classical canon, there are some key factors that seem to have influenced his currently unknown status in music history.

Fairchild spent much of his adult life abroad, serving as a diplomat in several places including Tehran, and later settling in Paris. He wasn’t part of a national school or movement, and he didn’t promote his music aggressively. Instead, he uplifted and supported those musicians around him– composers, performers, and artists alike. Many would be surprised to know just how large a part he played in the success of many influential musicians, both directly and indirectly– from Samuel Dushkin and Igor Stravinsky, to Nadia Boulanger and Aaron Copland. The thread of Fairchild’s influence within the fabric of life during that time is a long and intricate one, though while looking at the tapestry at large, he’s hidden and easy to miss.

His music can be described as late-Romantic while employing various features of the music that surrounded him in Paris (especially that of Debussy). At the same time (about 1910-1930), classical music was quickly transitioning away from late-romantic styles toward more experimental approaches (Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Bartok, Varese…). The general excitement about innovation meant that composers like Blair Fairchild were given little attention after the 1920s. And after his death in 1933, performances of his music waned significantly.

In some ways, he also existed in the margins of multiple worlds: too international to be fully embraced by the American musical establishment of his time, and, while highly regarded in Paris, he wasn’t French enough to be a direct part of French musical history. His compositional style and personal life was grounded in atmosphere, narrative, and cross-cultural inspiration—qualities that may not have fit neatly into the categories historians tend to use.

For us, that’s part of what makes his music so compelling today. While his placement in the convergence of Romanticism, Modernism, and Impressionism wouldn’t have struck historians as trailblazing, when looking back at the music of that time there is certainly value in its confluence. It invites us to expand our understanding of what the American and international classical tradition has been, and who gets remembered within it.

Read more below!

Dawning meets Lucia Miller in Chicago after series of letters and emails

Lucia Miller on Monhegan Island, with members of her family and our family, July 2016

Reawakening a Forgotten Voice:

The Music and Life of Blair Fairchild

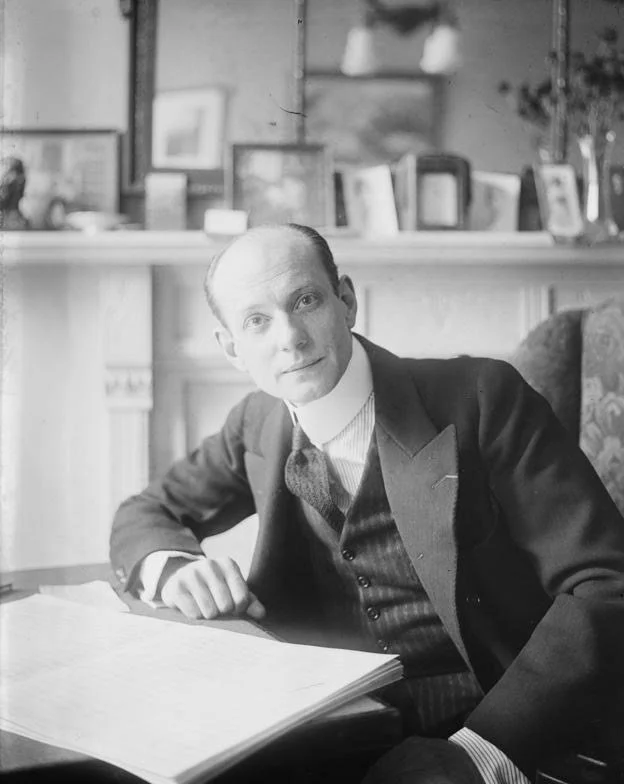

In the vast tapestry of classical music history, many threads have faded with time—composers whose voices once resonated across concert halls, now barely remembered. One such thread belongs to Blair Fairchild (1877–1933), a visionary American composer, diplomat, and world traveler whose works fused Western classical tradition with influences from Persia, China, Indigenous America, and beyond. Nearly forgotten for decades, Fairchild’s music is now beginning to re-emerge, intimate and intense, lyrical and fiery—echoing a creative spirit that refuses to be lost.

This project, the recording and release of Fairchild’s Sonata No. 1 for Violin and Piano, is the first step in a long-held dream of ours: to reintroduce the world to his music. My dad, David, and I first encountered Fairchild almost fifteen years ago, and I’ve been quietly carrying his story with me ever since—drawn by something in the contours of his melodies, and by the mystery of a life that bridged continents, cultures, and callings.

Who was Blair Fairchild?

Born into a prominent New England family (his sister Lucia became a celebrated painter), Blair Fairchild was raised in a world of privilege and purpose. He studied music at Harvard, then furthered his education in Europe under the guidance of composers like Charles-Marie Widor. But Fairchild was also a diplomat, stationed in Persia (modern-day Iran) in the early 20th century. His time abroad shaped him profoundly—both spiritually and musically.

Fairchild’s compositions reflect his international experience, blending French Impressionism with Eastern-inspired melodies and rhythms, all grounded in the language of late Romanticism. His music is elegant and exploratory—full of color, nuance, and drama. Even prominent performers, composers, and audiences of his time recognized its significance—yet after his death, performances of his work nearly disappeared.

Why Now?

There is something deeply timely about rediscovering Blair Fairchild. In an era hungry for cultural cross-pollination, for musical storytelling that transcends borders, his voice feels especially resonant. Fairchild was an early example of what we might today call a global artist—not just in the places he lived, but in the way his music listens to the world.

As a violinist and educator, I feel compelled to help surface voices like his—artists who stood at creative intersections, who defied categories, who made space for new musical conversations. My father and I have also always felt deeply touched by his devotion to supporting the careers of those around him who wouldn’t have thrived without his help. All accounts point to him being of selfless character, of gentle demeanor, and with a keen sense of justice.

The Sonata

This performance of Sonata No. 1 for Violin and Piano—with pianist Aleksandra Czerniecka and myself on violin—is just one of a series of efforts to reintroduce Fairchild’s catalog. It’s also part of a broader dream: to initiate further collaboration with many artists to perform and record his works and to honor his life’s work. Our goal is to create not just a tribute, but a living legacy.

This sonata’s first movement, Allegro con fuoco, is fiery and autumnal—like the blaze of a spirit both restless and refined. It felt like the right place to begin. Subsequent movements

What’s Next?

We invite you to listen—and to share. We’ll be releasing future movements, publishing newly uncovered works, and offering interviews, essays, and conversations about Fairchild’s life and artistic philosophy. If you’re a musician, researcher, or listener intrigued by this journey, we welcome your collaboration.

This is a labor of love, but also one of hope: that the voices we think are lost may still be heard.